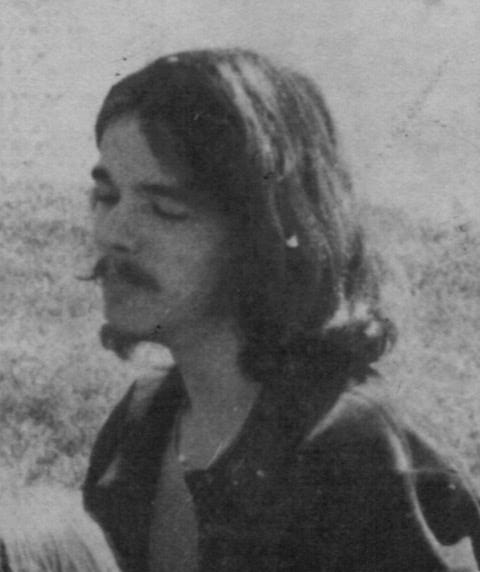

On May 14, 1972, a young soul was lost to the fatal combination of youth, drugs, bald tires, and stupidity. His name was Ronald David Erwin, and he was my best friend. I and my classmates knew him as “Mac.” The reasons he was my best friend I would not understand until much later in life.

The reasons, shallow teen reasons they were, that I understood at the time were that for years, we shared an intense interest in music and would spend hours wearing out the grooves of LP records. The Eagles, Led Zeppelin, Albert King, Simon and Garfunkel, hundreds of other artists, and our heroes, The Beatles.

Now, we were Seniors at Troy High School, poised to graduate in less than a month, both outsiders having no idea what our futures would be and no plans. We just wanted to get high, listen to and play music, and have fun. Neither of us would ever go to school again, and we liked it that way.

I had no discernible future. As a lazy and undisciplined student, I had no hope of being successful in college— as if I had a chance of being accepted with my grades.

Mac had a hard time fitting in. There was a rebel inside, not a destructive one, but one who dreamed of something better, more stable, safer. At the time, I did not know the origins of that, either.

Mac was a great singer and guitarist who mastered the folk genre of the times— Jackson Browne, Carole King, Gordon Lightfoot, but mostly, James Taylor. He would entertain in the school cafeteria, on the front steps, at the teen rec center, or anywhere else where someone would listen.

I could have fit in, but I didn’t want to. Being a faux hippie revolutionary was more to my liking. We were the outcasts at school, hated— we presumed— by the jocks, straights, and other cliques.

Decades later, I learned what made Mac who he was, and it isn’t pretty. Mac hid his home life very well, even though I was often at his house. I’d known him for six years and never knew his drunken father beat the hell out of him regularly. I never saw his father at the house and assumed his mother was a single parent.

Many times, he would step in front of his mother or siblings and absorb the punches on their behalf. During his performative rages, Daddy knew just where to land the blows so bruises would be hidden under clothing the following day at work or school. No split lips, no black eyes. I never knew.

When I left home at sixteen in defiance of expectations that I should behave like a decent human being and responsible family member, I crashed at an older guy’s rented house, got involved in more drugs and alcohol, and refused to attend school. Mac went to see my parents to alert them to the danger I was in and implored them to take me back. I lived a relatively normal middle-class life. His was a hellhole, but he was looking out for me. If I had known he went to see tham, I probably would have seen that as a betrayal. He took the risk.

Mac had a deep well of empathy for others who were troubled or in trouble. I learned this fifty years later at my high school reunion when we arranged a gathering for anyone who knew him to reminisce and share stories. Attending were classmates from all walks of school life, people I would not have imagined would attend. It turns out his generosity knew no bounds of clique or peer group, and stories of his grace and caring made me realize what a gem we had lost.

When I hear Fire and Rain, Carolina on My Mind, You Can Close Your Eyes, or dozens of other songs from the era, I often feel a pang of loss, as I am right now, not just for me but for all the potential that was lost at the passing of Ron Erwin. He was a major talent, one that might have gone anywhere. More important, he rose above horrible circumstances to become an exemplary man at eighteen.

Great songwriting, such as Fire and Rain, achieves its power through suffering and loss, experiences Mac had in unfortunate plentitude. But it might have made him an artistic superstar had he lived to escape his circumstances and have the freedom to live in peace.

I was lucky to have him for six years, and for that, I will never forget to be grateful.

It took some time for friendship to take hold after first meeting you. That was back in Miami around 1977. Conditions were adversarial but the bond was formed quickly. I became aware of the physical pain and sorrow you were enduring after a while but you kept details fairly vague. Nearly 50 years on, I am witness to your physical suffering and now, finally, understand the rest. While you claim not to remember much about many things, I'm happy for you that this memory, painful though it is, has not faded. And that you could honor your friend Mac in the beautiful words you have written.

Thank you for sharing this J.C. I knew Ronnie for not even 2 years and have grieved over 50 years. It is not fair. He was gifted, kind and old beyond his years. "Look on down from the bridge, I'm still waiting for you" (Mazzy Star) 💔😭